Q 1. What is pelvic organ prolapse?

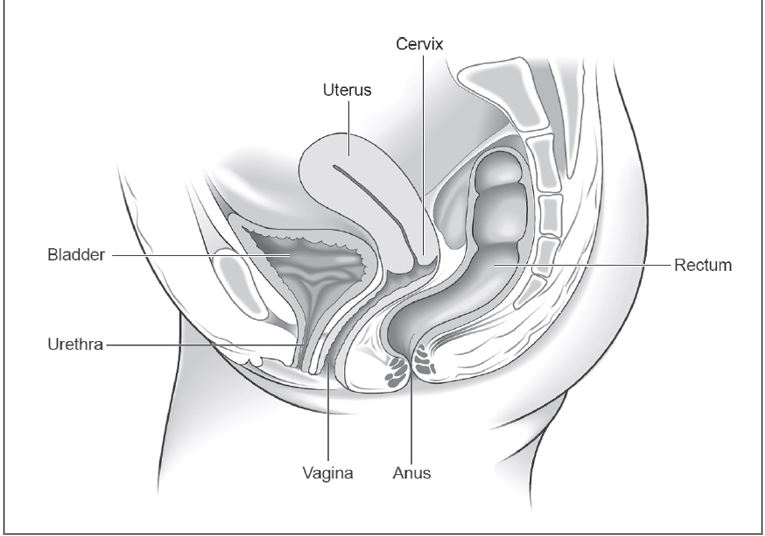

A. The organs within a woman’s pelvis (uterus, bladder and rectum) are normally held in place by ligaments and muscles known as the pelvic floor.

If these support structures are weakened by overstretching, the pelvic organs can bulge (prolapse) from their natural position into the vagina. When this happens, it is known as pelvic organ prolapse. Sometimes a prolapse may be large enough to protrude outside the vagina.

Q 2. How common is pelvic organ prolapse?

A. It is difficult to know exactly how many women are affected by prolapse since many do not go to their doctor about it. However, it does appear to be very common, especially in older women.

Half of women over 50 will have some symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse and by the age of 80 more than one in ten will have had surgery for prolapse.

Q 3. Why does pelvic organ prolapse happen?

A. Being pregnant and giving birth are the most common causes of weakening of the pelvic floor, particularly if:

- Your baby was large

- You had an assisted birth (forceps/ventouse) or

- Your labour was prolonged.

- The more births a woman has, the more likely she is to develop a prolapse in later life; however, you can still get a prolapse even if you haven’t given birth. Performing pelvic floor exercises is very important after childbirth but may not prevent prolapse from occurring.

- Prolapse is more common as you get older, particularly after the menopause.

- Being overweight can weaken the pelvic floor.

- Constipation, persistent coughing or prolonged heavy lifting can cause a strain to the pelvic floor and can cause pelvic organ prolapse.

- Following hysterectomy, the top of the vagina is supported by ligaments and muscles. If these supports weaken, a vault prolapse may occur (see below).

- It is possible to have a natural tendency to develop prolapse.

Often it is a combination of these factors that results in you having a prolapse.

Q 4. What are the different types of prolapse?

A. There are different types of prolapse depending on which organ is bulging into the vagina. The uterus, bladder, or rectum may be involved. It is common to have more than one type of prolapse at the same time.

Normal pelvic anatomy looks like this:

The most common types of prolapse are:

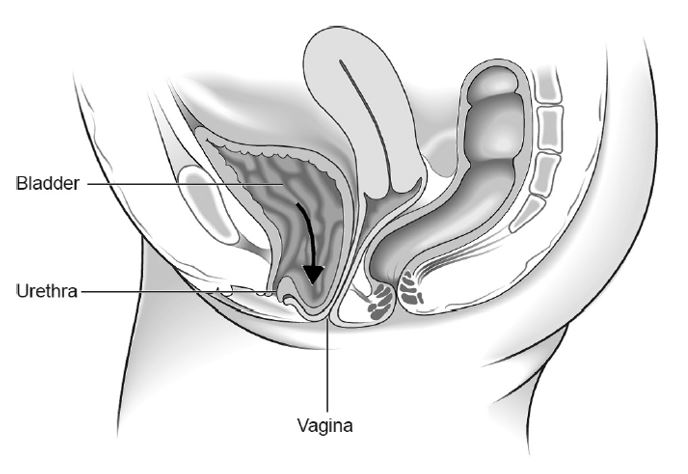

- Anterior wall prolapse (cystocele) – when the bladder bulges into the front wall of the vagina.

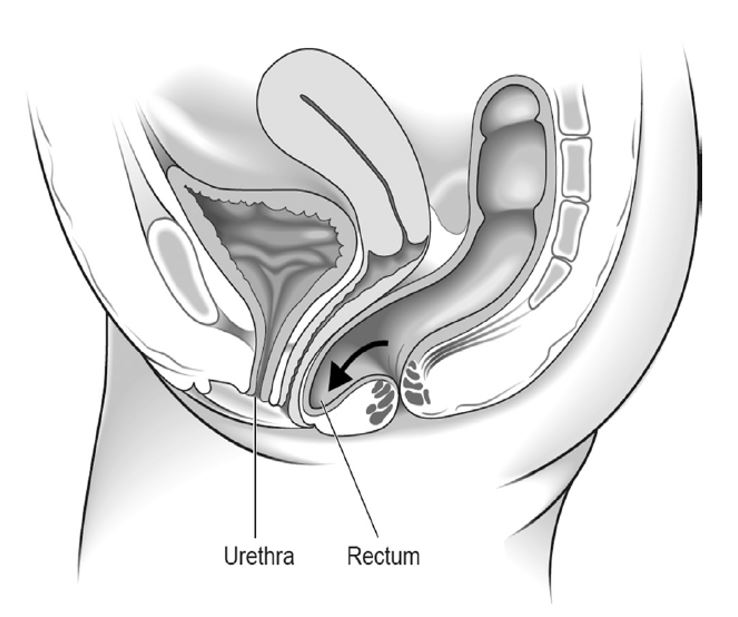

- Posterior wall prolapse (rectocele) – when the rectum bulges into the back wall of the vagina.

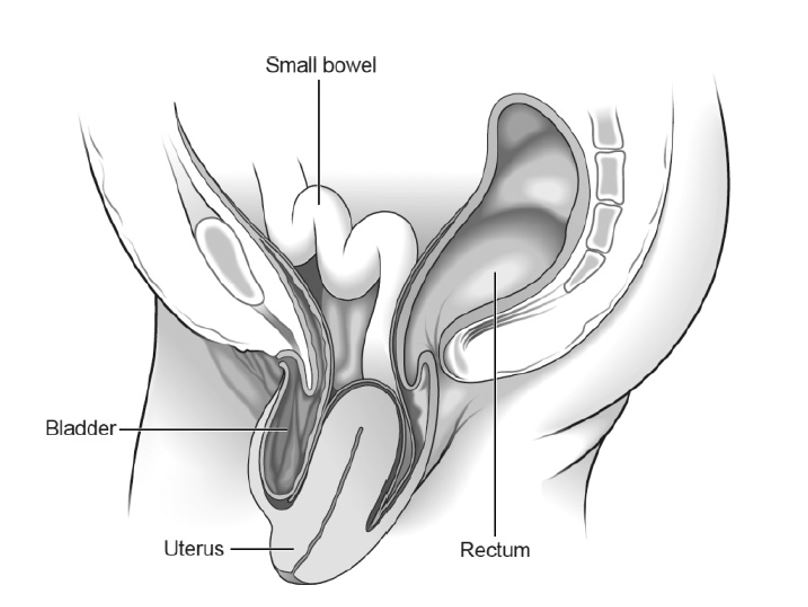

- Uterine prolapse – when the uterus hangs down into the vagina. Eventually the uterus may protrude outside the body. This is called a procidentia or third-degree prolapse.

- Vault prolapse – after a hysterectomy has been performed, the top (or vault) of the vagina may bulge down. This is called a vault prolapse. This happens to one in ten women who have had a hysterectomy to treat their original prolapse.

There are different degrees of prolapse depending on how far the organ(s) have bulged. It is important to distinguish between the various types and degrees of pelvic organ prolapse as their symptoms and treatment may differ.

Q 5. What are the symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse?

A. Your symptoms will depend on the type and severity of your prolapse.

- You may not have any symptoms at all and may only find out that you have a prolapse after a vaginal examination by a healthcare professional, for example when you have a smear test. A small amount of prolapse can often be normal.

- The most common symptom is the sensation of a lump ‘coming down’. You may also have had backache, heaviness or a dragging discomfort inside your vagina. These symptoms are often worse if you have been standing (or sitting) for a long time or at the end of the day. These symptoms often improve on lying down.

- You may be able to feel or see a lump or bulge. You should see your doctor if this is the case because the prolapse may become sore, ulcerated or infected.

- If your bladder has prolapsed into the vagina, you may:

- Experience the need to pass urine more frequently

- Have difficulty in passing urine or a sensation that your bladder is not emptying properly

- Leak urine when coughing, laughing or lifting heavy objects

- Have frequent urinary tract infections (cystitis).

- If your bowel is affected, you may experience low back pain, constipation or incomplete bowel emptying. You may need to push back the prolapse to allow stools to pass.

- Sex may be uncomfortable and you may also experience a lack of sensation during intercourse.

Q 6. How is prolapse diagnosed?

A. Prolapse is diagnosed by performing a vaginal examination.

Your doctor will usually insert a speculum (a plastic or metal instrument used to separate the walls of the vagina to show or reach the cervix) into the vagina to see exactly which organ(s) are prolapsing.

You may be asked to lie on your left side with your knees drawn up slightly towards your chest in order to for this examination to be performed. You may also be examined standing up.

Q 7. Will I need any tests?

A. You may have had a urine test to check for infection. If you have bladder symptoms, particularly if you leak when you cough or laugh, you may be referred for special bladder tests known as urodynamics. These are usually done in a hospital.

Q 8. Do I have to have treatment?

A. No.

If you only have a mild prolapse or have no symptoms from your prolapse, you may choose or be advised to take a ‘wait and see’ approach.

However, the following may ease your symptoms and stop your prolapse from becoming worse:

- Lifestyle changes

- Losing weight if you are overweight

- Managing a chronic cough if you have one; stopping smoking will help

- Avoiding constipation; talk to your doctor about ways of helping and treating constipation

- Avoiding heavy lifting; you may wish to talk to your employer if your job involves heavy lifting

- Avoiding physical activity such as trampolining or high-impact exercise.

- Pelvic floor exercises may help to strengthen your pelvic floor muscles. You may be referred for a course of treatment to a physiotherapist who specialises in prolapse.

- Vaginal hormone treatment (oestrogen) – if you have a mild prolapse and you have gone through the menopause; your doctor may recommend vaginal tablets or cream.

Q 9. What are my options for treatment?

A. Your options for treatment will depend on the type of prolapse you have; how severe it is and your individual circumstances. Treatment options include the following.

Pessary

- A pessary is a good way of supporting a prolapse.

- You may choose this option if you do not wish to have surgery, are thinking about having children in the future or have a medical condition that makes surgery riskier.

- Pessaries are more likely to help a uterine prolapse or an anterior wall prolapse, and are less likely to help a posterior wall prolapse. The pessary is a plastic or silicone device that fits into the vagina to help support the pelvic organs and hold up the uterus.

- There are various types and sizes; your doctor will advise which one is best for your situation.

- The most commonly used type is a ring pessary.

- Fitting the correct size of pessary is important and may take more than one attempt.

- Pessaries should be changed or removed, cleaned and reinserted regularly. This can be done by your doctor, nurse or sometimes by yourself.

- Oestrogen cream is sometimes used when changing the pessary, particularly if you have any soreness.

- Pessaries do not usually cause any problems but may on occasion cause inflammation. If you have any unexpected bleeding, you should see your doctor.

- It is possible to have sex with some types of pessary although you and your partner may occasionally be aware of it.

Surgery

The aim of surgery is to relieve your symptoms while making sure your bladder and bowels work normally after the operation. If you are sexually active, every effort will be made to ensure that sex is comfortable afterwards.

Whether you choose to have surgery will depend on how severe your symptoms are and how your prolapse affects your daily life. You may want to consider surgery if other options have not adequately helped.

There are risks with any operation. These risks are higher if you are overweight or have medical problems. Your gynaecologist will discuss this with you so that you can decide whether you wish to go ahead with your operation.

If you plan to have children, you may choose to delay surgery until your family is complete. If you do undergo surgery, you may be advised to have a caesarean section if you become pregnant.

Q 10. What are the different types of surgery for pelvic organ prolapse?

A. There are many different operations that can be performed to treat prolapse. Your gynaecologist will advise you which operation is best for you. This will depend on your type of prolapse and your symptoms, as well as your age, general health, wish to have sexual intercourse and whether or not you have completed your family.

If there is more than one choice, your gynaecologist will explain the pros and cons of each.

Surgery for prolapse is usually performed through the vagina but may involve a cut in your abdomen or keyhole surgery. If your gynaecologist is not able to offer the operation that best meets your needs, you may be referred to a specialist unit. New surgical techniques are being developed all the time. You should talk to your gynaecologist to find out whether there is anything new that might be more suitable for you.

Possible operations include:

- Pelvic floor repair: If you have prolapse of the anterior or posterior walls of the vagina (cystocele or rectocele); this is where the walls of your vagina are tightened up to support the pelvic organs. This is usually done through your vagina so you do not need a cut in your abdomen. In recent years a number of new operations have been developed where mesh (supporting material) is sewn into the vaginal walls. The risks and benefits of mesh are unclear.

- Operations that aim to lift up and attach your uterus or vagina to a bone towards the bottom of your spine or a ligament within your pelvis (sacrocolpopexy or sacrospinous fixation). These may be done by keyhole surgery.

- Vaginal hysterectomy (removal of the uterus): It is sometimes performed for uterine prolapse. Your gynaecologist might recommend that this be performed at the same time as a pelvic floor repair.

- Colpocleisis (Closing off your vagina): It may be considered but only if you are in very poor medical health or if you have had several operations previously that have been unsuccessful. Vaginal intercourse is no longer possible after this operation.

It may be possible to treat urinary incontinence at the same time as surgery for prolapse and your doctor will discuss this with you if relevant.

Sometimes when you are relaxed under the anaesthetic, other areas of prolapse can become obvious. Your surgeon may request your consent to operate on those areas of prolapse as well. This should be fully discussed with you before your operation.

Q 11. How successful is surgery for pelvic organ prolapse?

A. No operation can be guaranteed to cure your prolapse, but most offer a good chance of improving your symptoms. The benefits of some last longer than others.

About 25–30 out of 100 women having surgery for prolapse will develop another prolapse in the future. There is a higher chance of the prolapse returning if you are overweight, constipated, have a chronic cough or undertake heavy physical activities. Prolapse may occur in another part of the vagina and may need repair at a later date.

Q 12. What might happen if I don’t have an operation?

A. Your problems may remain the same or get worse, or sometimes even improve over time. There is no way of confidently predicting this but an advanced prolapse cannot be expected to improve without a pessary or surgery. Prolapse is not life-threatening although it may affect the quality of your life. You can reconsider your options at any time.

Q 13. Is there anything else I need to know?

A. The length of time you need to spend in hospital after the operation will vary depending on the type of operation and how quickly you recover, but will usually be no more than a few days. Generally speaking, you should avoid heavy lifting after surgery and avoid sexual intercourse for 6–8 weeks.

Q 14. What are the key points to remember?

A. The key points to remember are:

- Prolapse is very common. Mild prolapse often causes no symptoms and treatment is not always necessary. However, you should see your doctor if you think you may have a prolapse.

- Prolapse can affect quality of life by causing symptoms such as discomfort or a feeling of heaviness. It can cause bladder and bowel problems, and sexual activity may also be affected.

- Prolapse can be reduced with various lifestyle interventions interventions including stopping smoking, weight loss, exercise and avoiding constipation, as well as avoidance of activities that may make your prolapse worse such as heavy lifting.

- Treatment options to support your prolapse include physiotherapy, pessaries and surgery.

- How severe your symptoms are and whether you choose to have surgery will depend on how your prolapse affects your daily life. Not everyone with prolapse needs surgery but you may want to consider surgery if other options have not adequately helped.

- Surgery for prolapse aims to support the pelvic organs and to help ease your symptoms. It cannot always cure the problem completely. There are a number of possible operations; the most suitable one for you will depend on your circumstances.